There follows an extensive interview between Creative Review and johnson banks' Michael Johnson about the state of the branding world, and the background to his new book. You can also read it on the CR blog.

CR: Why another book on branding? What is the gap you are trying to fill?

MJ: Over the last decade or so, johnson banks has spent most of its time working on brand identity projects, but every now and again I’d look to double-check our ‘process’ against others and there was remarkably little out there that would really help. The books that are available tend to fall into two distinct categories - on one side those concentrating on strategy, on the other, design. I found what’s on offer to be either flawed, or limited in scope.

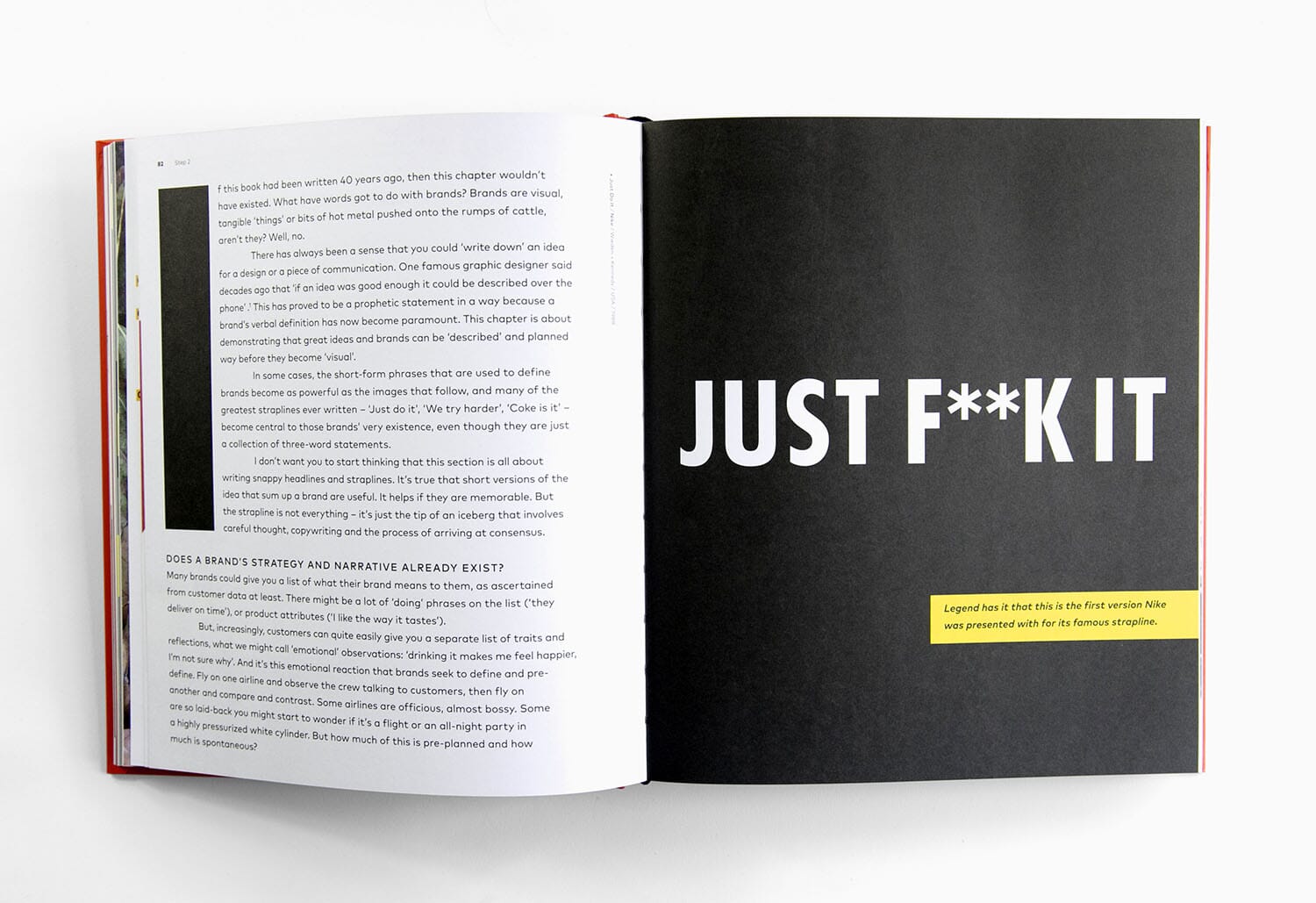

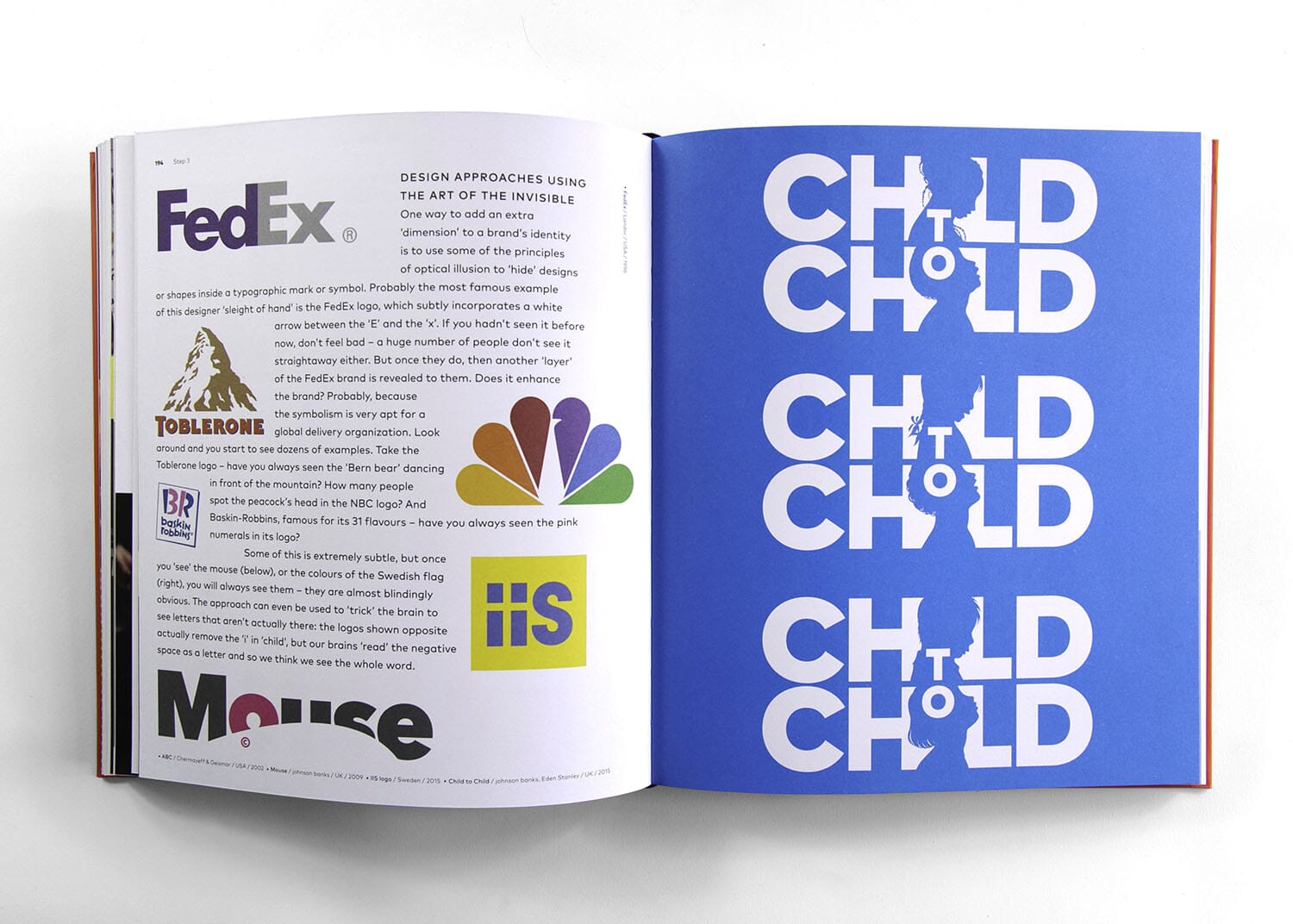

The strategy books either concentrate on ‘the things I learned whilst marketing director of a huge multinational’, or offer up some form of branding ‘model’ which often aren’t very grounded in the day-to-day of branding projects. The design bookshelves groan with tomes on symbols and logotypes, but very few of them give the reader any insight into the process of designing them. They are nearly always crammed with ‘final product’, useful sometimes for skipping through for inspiration but you rarely actually learn much from them.

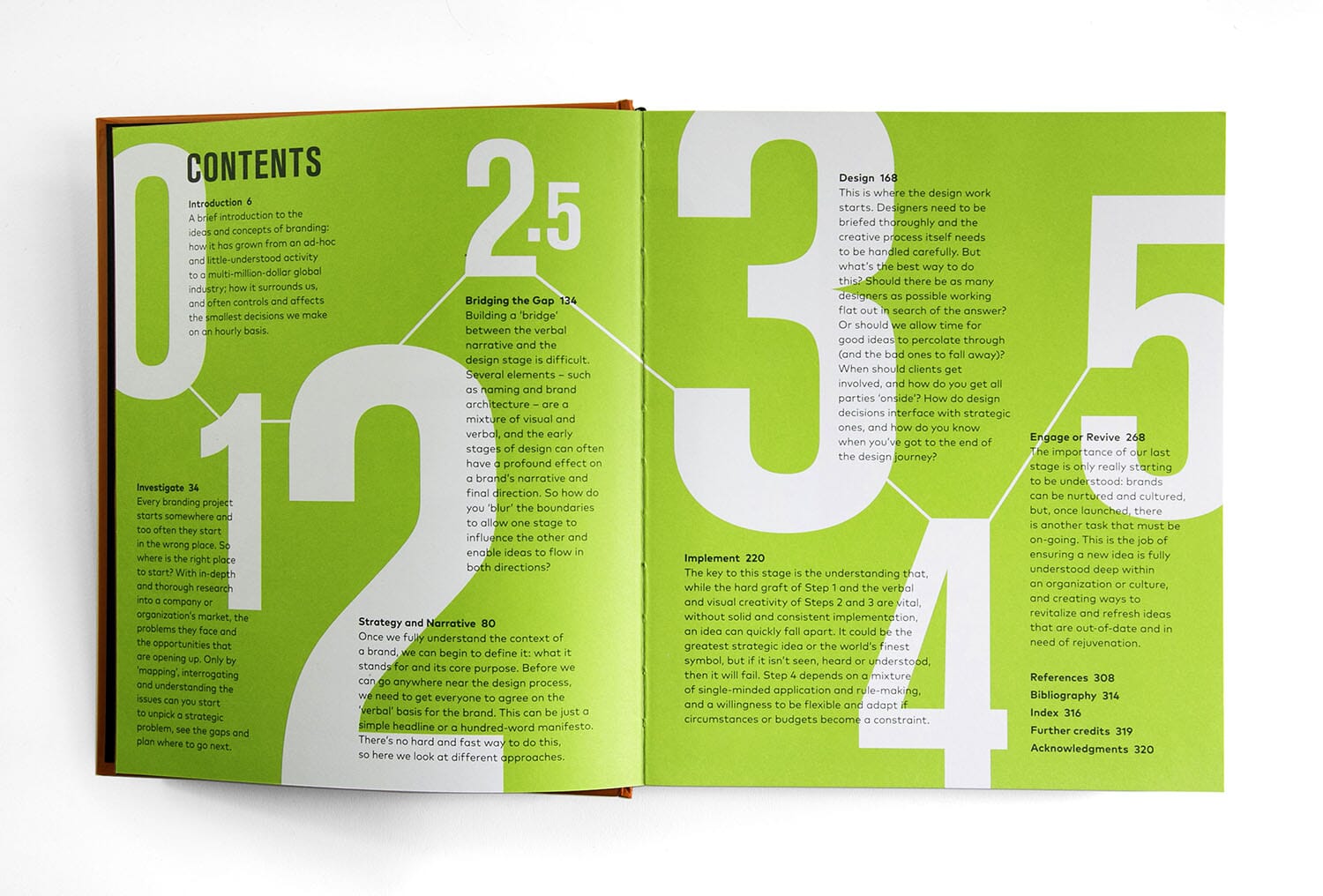

So about 2.5 years ago I started work on a synopsis of a book that explained both sides of the process – yet was of interest to both. A strategist or planner should glean a lot from the first half - but might keep reading the second half. Conversely a lot of designers are, I’m certain, looking to understand the business side more, but are probably put off by what’s available at present.

CR: You have five and a half steps in the book – can you explain what your half step is and its importance?

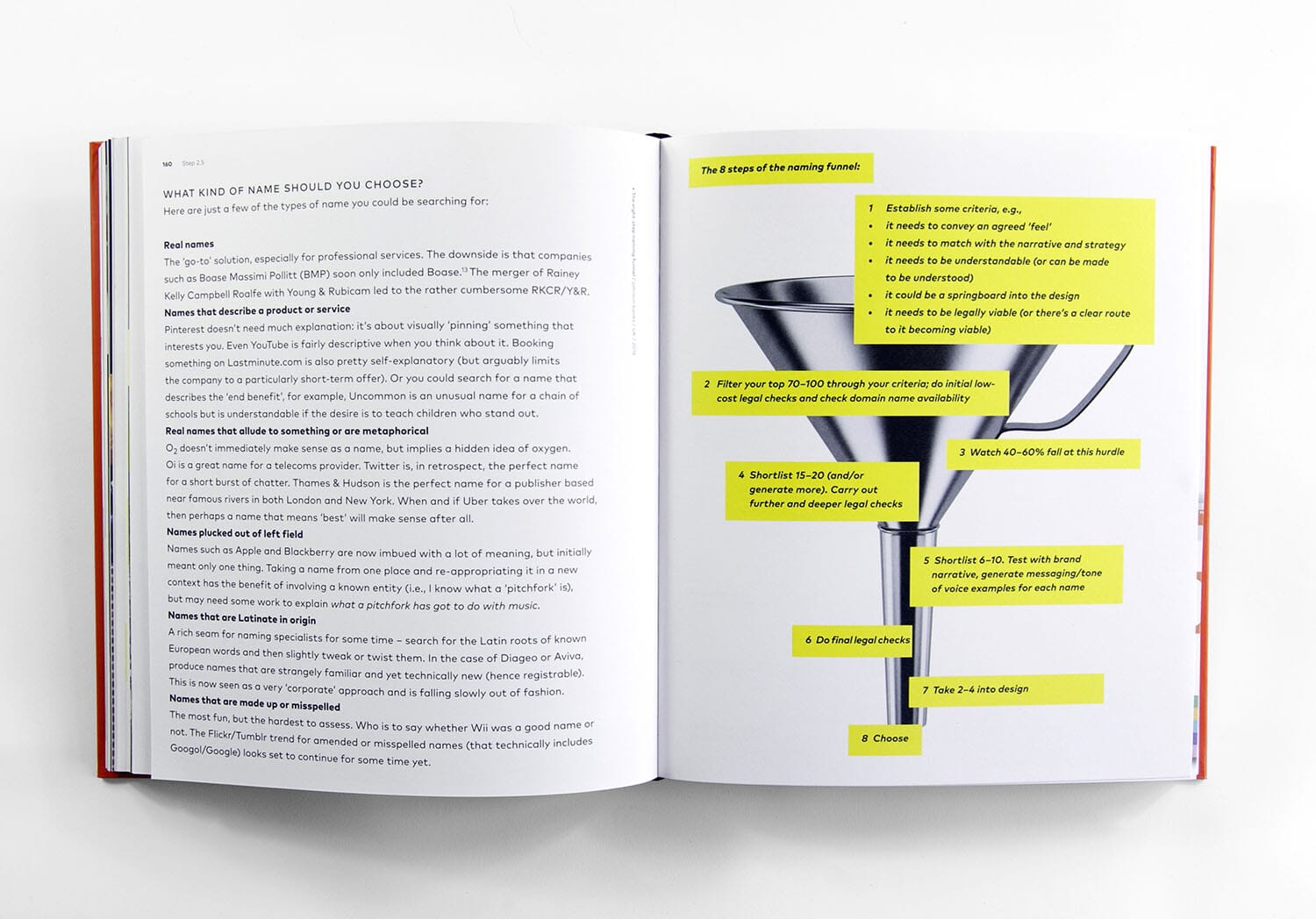

MJ: As I started to plan out the five steps of the process, Research, Strategy and Narrative, Design, Implementation, Embedding and Reviving, I started to realise that certain parts of the process didn’t fall naturally into either step 2 (strategy) or step 3 (design).

This was also echoed by multiple projects in my day job where the line between steps two and three started to blur. For example, several projects were effectively ‘solved’ by innovative approaches to brand architecture (e.g. our Pew Center project) - now was that design, was it strategy, or was it both? We also began to see that the naming of our projects was clearly vital - but the names were often explored in tandem with designs - i.e. strategy, naming and design were done in parallel.

Since starting to write about this ‘blur’ between stages, I’ve had many intriguing conversations with peers and colleagues who have also realised that the ‘translation’ of one side into another is often key to a project’s success - so by writing about this I hope others will begin to appreciate this too.

CR: How can we improve public perceptions of branding and in particular of the value of rebranding organisations?

MJ: It’s true that the red-tops and often the broadsheets still start a feeding frenzy when a major organisation rebrands. I think this is down to a series of factors. The whole business is guilty of not explaining the breadth and depth of the process - so the public just see the tip of the iceberg of a scheme and rarely appreciate all that lies underneath. Another issue is internal management - companies are worried about how ‘change’ will be perceived and often keep it all under lock and key - then batten down the hatches when the change is finally made public.

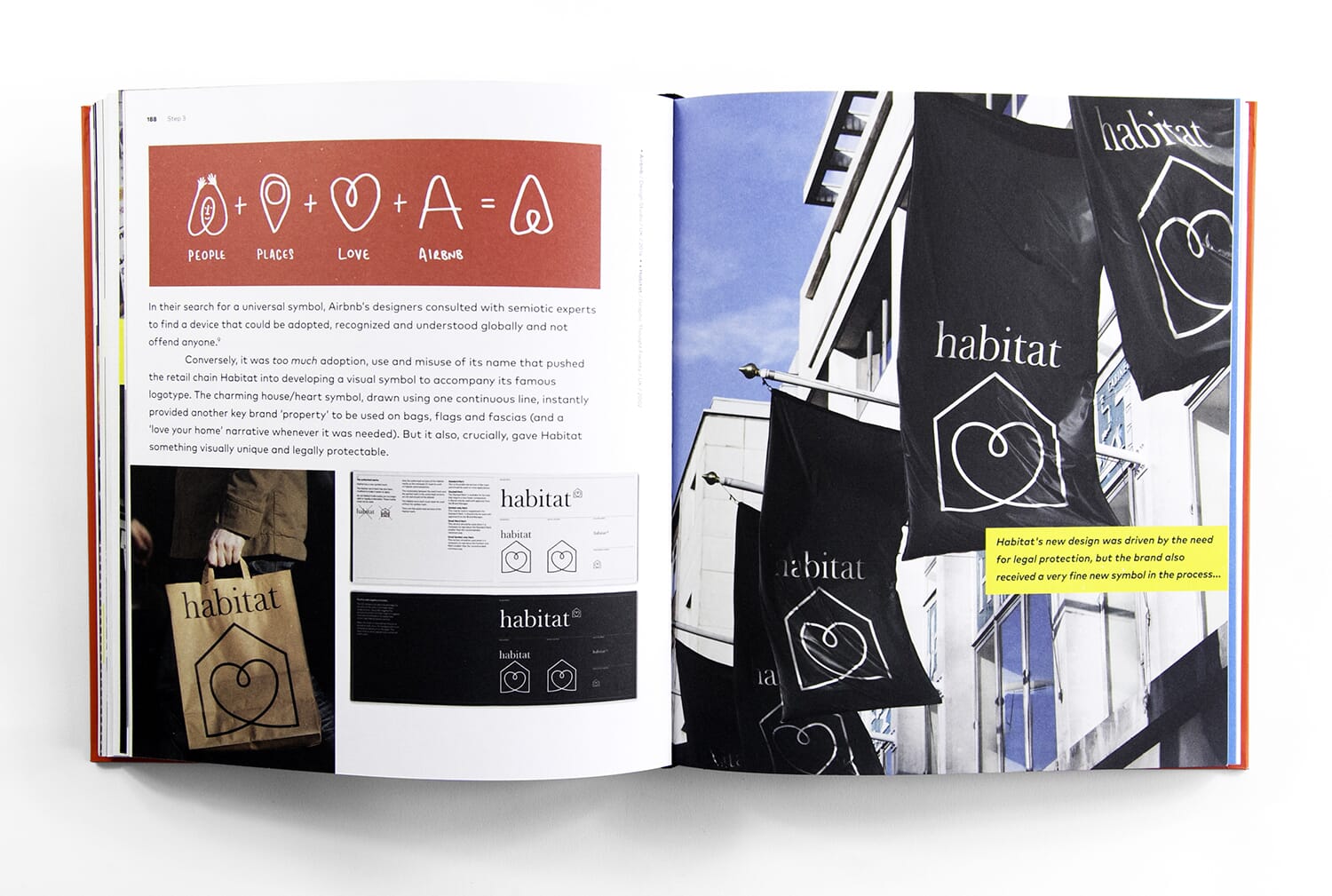

Perhaps by forcing the branding process out into the open with this book, unravelling the jargon and opening up branding’s somewhat proprietorial black boxes, I’m taking a small step towards greater understanding. We’re also starting to see companies prepare themselves and plan for the furore and react accordingly - I thought Airbnb managed their rebrand well, for example.

The other key to this is that we have to get better at explaining that branding works. When I started doing what I do, it almost seemed gauche to have figures on the screen and to link raised awareness, funds raised, turnover changes to branding (and rebranding). I even wince a little myself when I get to my ‘proof’ slides. But, often, the numbers are hugely impressive and I should use them more, and apologise less.

CR: What has been the impact of such very public outcries as ‘Gapgate’ and the furore around the Met redesign on client attitudes and the way in which branding projects are managed?

MJ: Gapgate was a truly extraordinary example of what seems to be corporate bungling at the highest level - a proposed logo is leaked, there’s an online backlash, the client then seems to pretend it’s sounding people out on the change, then withdraws it. Unfortunately, Gap is still saddled with a blue square and some squashed Bodoni-esque type, that it has had for too long, and really needs to change, but can’t. The Met re-design is simply that, a re-design that didn’t ‘evolve’ at all from the old and consequently ruffled feathers.

The impact of these two examples? Gapgate probably made some more fearful of change, yet illustrated perfectly that if change is needed, it needs to be planned carefully. The Met example is, in my view, one of a cultural organisation wanting to present a new face, to update its approach, and probably reach out to different visitors. Now, the new logo may not be your thing, but it certainly will have made some people look at them differently.

The harsh truth of the current internet environment is that whatever you do, whether you’re a journalist for the Guardian, a politician, a brand consultant - you’re going to get trolled. We’re an easy target, and just at the moment ‘direct feedback’ is the norm. The truth is, much of it dies down within weeks, sometimes days. Human beings are programmed to resist change - yet we adapt remarkably quickly.

CR: If you look at the online comment from designers on each others’ work, where peers are routinely accused of doing very little for their money, of the post-rationalisation of their work and of providing the thinnest of rationales for their projects, why is it that so many designers seem to think that their colleagues in the branding world are charlatans?

MJ: Ha. Yes I’ve lost count of the times I’ve been accused of being a snake-oil salesman! It is odd that designers will routinely destroy, sometimes in public, other designers’ work. It’s a noxious mix of misunderstanding, jealousy, rage, and perhaps symptomatic of the lack of confidence or indeed professionalism of the business.

There’s no easy fix for this. First of all, it’s my view that new projects deserve far deeper explanation and narrative than most are currently given, so observers are forced to understand the background to a project. But the early stages of the narrative work on our Mozilla project received a few dozen responses, when we got to logos the commentary quickly ramped up by about 1000%. Even when the rationale is there, it doesn’t mean that it is read.

Secondly I think the profession needs to grow up a little and accept that it’s a broad church – you don’t have to ‘like’ everything. I regularly use other peoples’ projects to illustrate a point in lectures or presentations - pretending that ‘no-one else works the way we do’ is a bit mealy mouthed and somewhat delusional.

Thirdly I think some of the dogma of the previous generations need to be examined more carefully - I’m all for ‘less is more’ and boil me down and I’m probably a closet modernist, but that doesn’t mean I have to do every project in Helvetica and criticise others for not following pre-ordained rules. Designers should be better at accepting that just because something doesn’t echo their aesthetic, it has to be wrong.

Fourthly, and this one is tougher to crack, I think that the teaching in colleges has to try and be a little more worldly. It has to accept that branding is not going away and encourage its students to think way, way deeper than just designing one logo for themselves in one module and pretending that’s ever going to be enough.

Lastly I think the profession has to learn to use real words and genuine rationale that really explains what they have done, why, and for what purpose. Surrounding projects with impenetrable rationale does open us up to criticism or make us sound like we’re writing the next scripts for W1A.

CR: Many branding projects are implemented, at least in part, by third parties – either in-house teams or other designers brought in to handle specialist applications. In the modern world of flexible brands, how do you ensure that the implementation of a brand stays true to the original intention of the work?

MJ: Nearly two decades ago I remember interviewing Neville Brody and he said the first thing he did on big projects was ensure that they had in-house designers. At the time, I didn’t really ‘get’ that point - I think I still thought that we, the designers, would both initiate then do, everything. Obviously what has changed, hugely, over the last decade or so is that in-house teams, or a second wave of designers often do the actual implementation. Project such as our recent University of Cambridge project, with hundreds of applications written, designed, filmed and animated by ourselves over a hectic three-month whirlwind are now quite rare.

As a result, we’ve had to become quite adept at shepherding ideas through into reality and keeping as much of the initial oomph as possible. We learned early that any kind of consultant vs in-house stand-off was always a bad idea and try as hard as we can to get all parties working together. Workshops, shared projects, anything and everything. We’ve often had client design teams in at johnson banks to work on projects here - that seems to work well. It’s my view that any ‘manuals’ that are produced should be wide-ranging and provide quite a bit of inspiration (although certain types of client still want some very strict rules!)

Eventually, your carefully crafted brand leaves you and enters into the unknown. And there’s a key point where it could fail - it’s now a big part of our job to ensure that it won’t. The notion of inbuilt flexibility within a brand is, I still think, a valid one - but we’ve certainly had people interpret designed-in flexibility in completely the wrong way, so the jury’s out on that.

What’s key is that a scheme moves from being a nice set of visuals (but in essence, virtual) to a real, genuine set of really good applications, and ideally way better than the virtual examples. I can smell those made-up, ‘never actually made it into production’ projects a mile off I’m afraid…

CR: What are the benefits and pitfalls of involving ‘stakeholders’ in the branding process, from strategy to design execution? (I guess your Mozilla project has a lot of relevance here)

MJ: For a long time now, the research side of what we and many other branding companies do has involved in-depth consultation. Usually this means interviews and workshops, talking to key people, getting their views, often building the case for a strategic direction (or sometimes, discovering a new one). Most big branding projects and re-brands involve key directors, boards, trustees… This is a process that can take months, usually repeats in the strategic stage, and in the design stage too.

There’s method in this - everyone get’s their say. So when we get to the visual stage, project teams have tracked the work. They’ve been involved, they’ve been listened to and are far more likely to be good ambassadors when it launches.

Of course, showing final design routes to a wide group brings with it the danger of committee decisions - this means the core project team (both client and consultant side) have to stay pretty tough. So what you’re seeing with the Mozilla project is a client with a huge amount of stakeholders saying ‘we want them to have their say’ - I guess a logical conclusion to come to, especially when they work in an open-source business. Rather than taking on, say, twenty different views, we now have two thousand. That makes things interesting!

CR: Now that there is so much emphasis on collaboration with clients, is the Paul Rand-doctor/patient model that so many designers still seem to cling to dead? How much are projects in effect co-created these days?

MJ: Well, many of us were brought up on that ‘I the designer will now unveil my creation and you the client will love it’ model, but it’s true that one-person, well-funded, design-loving patrons with no board to answer to and no KPIs to hit are in pretty short supply these days.

By making clients part of the process - many of whom have their own equally valid ideas, and many of whom also trained in either design or marketing (sometimes both) - it’s much more realistic to see it as co-creation. I think most smart designers have wised up to this now. I’m certainly very willing to acknowledge that several of our key projects over the last few years such as Acumen and now Mozilla, are effectively better products because of that collaboration.

More and more we and our clients are using the strategy and design process as effectively scenario-planning for entire corporate futures - and we can all see that the depth of this kind of design thinking can be enormously useful at the highest level. For example, our rebrand a few years ago of the DEC reached a key pivot point, where the new brand could either reflect the members of the organisation (who they are and what they do) or their umbilical link to disasters and emergencies (the ‘why’). They correctly chose the latter.

There’s another issue at play here too - go to any design conference and often designers mumble through their slides and make it appear that their ideas arrived, as if by magic, out of thin air. Working designs are rarely shown. Mistakes and blind-alleys? Almost never - because we’re never wrong? So the myth of the ‘aha’ moment where the genius designer ‘cracks it’ is perpetuated, even when it’s mostly a lie. So in the last 17 years I can name just two logos that came as ‘ahas’ on the first day - Shelter and More Th>n. The other, er, hundred or so were a result of hard, honest graft and the daily grapple to find something good and hopefully great. I’m certainly not blameless here either: I’ll often edit my conference slides so the ‘strategy’ is skipped through to get to ‘the design bit’, thinking that as visual people designers will be bored by the words and want pictures. Perhaps that needs a reboot too. Of course, the whole idea of my book is to share the whole process, warts and all, and to explain why routes were chosen, and why. Rationale is always included, at a readable size, not buried in 7-point captions.

CR: What has been the impact of the current trend for ‘brand purpose’ and the sudden desire for brands to be seen to be doing ‘good’?

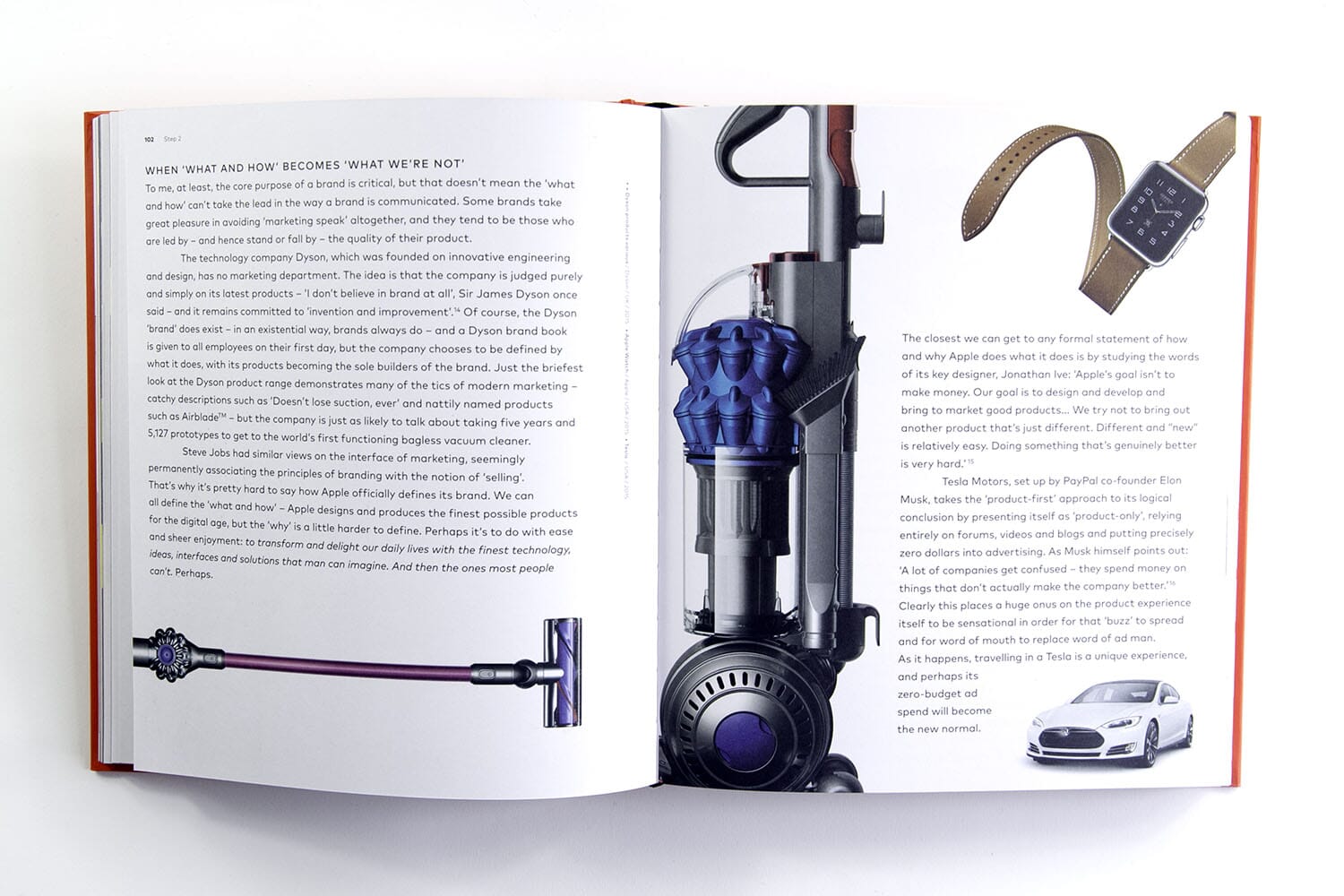

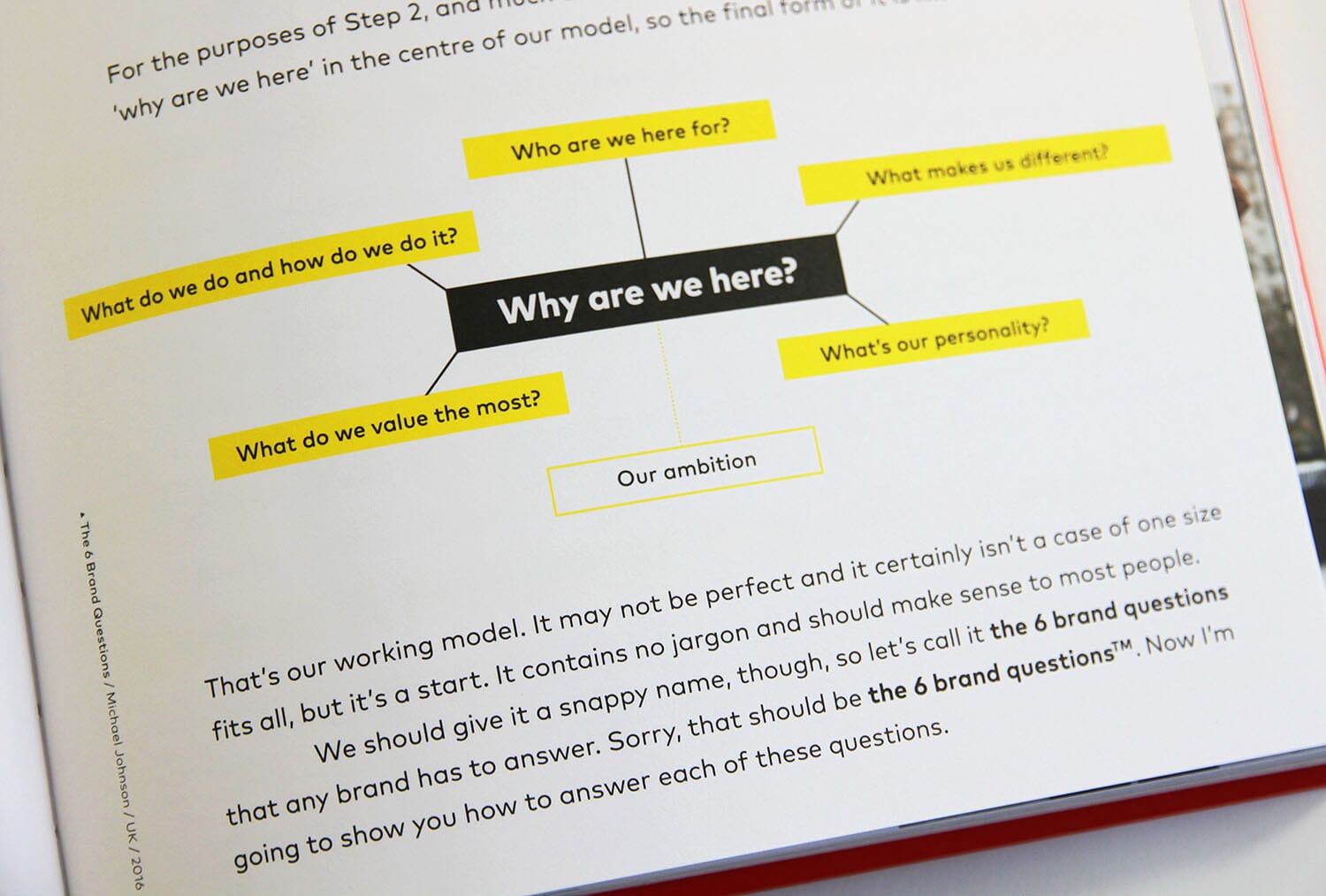

MJ: I think what you’re seeing is a lot of organisations finally realising that having ‘a reason to be’ or being able to state ‘why are we here’ is a far better model than what preceded it. The traditional terms of ‘mission’ and ‘vision’ either seemed overly militaristic, or overly lofty – I’m all for people and especially employees having a far clearer sense of ‘why’? If every Monday morning begins with the assertion that ‘we’re here to make lots of money for our bosses’, well that just doesn’t fly any more.

Finding a clearer ‘purpose’ certainly fits well with the majority of the work we do, which is biased to the educational, not-for-profit, ethical investment and cultural sectors, people who you would hope have a valid reason to be. Where I start to get a little queasy is when I see major corporations (who clearly aren’t doing much ‘good’, to be honest) trying to persuade us that they really are lovely people underneath and their detergent is actually saving the planet (or whatever). Maybe what this discussion will do is create a next generation of companies with a strong and believable idea right at the core of what they do - in fact we’re already starting to see this happen.

In the book I have proposed a brand model which asks 6 simple questions - I debated this long and hard with myself and toyed with the thought of sharing all the different brand models (there are a lot). Eventually, I decided that if you layered them on top of each other, they all broadly say the same thing - so I guess I’m proposing a kind of universal model, and putting that out there as an open-source model for all to use and adapt.

As for the movement towards ‘good’, well we’ve been working in these sectors now for 15 years. A decade ago, the idea of doing a major scheme for a charity would not have been taken seriously, or would have been done as a side-project – and there were virtually no case studies of any rigour to refer to. Now companies are scrambling over themselves to show that they can do ‘design for good’ and the not-for-profit and cultural sectors are now where the cutting edge branding schemes are being done. My hope is that eventually, finally, the blue-chips will wake up and realise that they don’t have to be quite as risk averse and realise that they too can invigorate their brands with clarity allied to powerful brand identity.

CR: Are current award show judging methods adequate for evaluating the worth and quality of branding projects?

MJ: Not really. Most are still primarily concerned with the surface ‘look’ of a scheme, make little more than a cursory nod to the projects’ backgrounds and rarely include clients on their juries. Historically, design juries are almost the worst people to judge if a branding scheme is significant, groundbreaking and will have historical impact. Let’s take our schemes for Shelter, the Science Museum and Cambridge, or Wolff Olins’ schemes for Tate, PRODUCT (RED) and Macmillan? All, I would argue, important schemes, yet, none of them won yellow pencils.

Now I’m not advocating that all award schemes should start giving prizes to ‘bad’ design, but some deeper knowledge of why a change took place, and what they were trying to do would help enormously. Conversely, some schemes concern themselves with the effectiveness of the work, and give out prizes to work that most of us would deem average, yet which produced (on paper) impressive results. It’s a tricky line to navigate.

I think there’s another issue at play here, which is the tendency for some design companies to ‘select’ branding projects entirely for awards purposes, perhaps even doing them at vastly reduced rates, or even giving them away pro-bono. The implicit trade here being that the client will let them do ‘something good’ in return.

Firstly, this doesn’t fit with our business model - we have to charge something for what we do otherwise we’d go under. And I find the ‘this nice little charity job could be our pencil-winner’ idea borderline offensive. We’ll never start any project thinking it could win awards - we’ll just start it trying to do the best job we possibly can, the appreciation can come later, if ever. When something as nuts and bolts as our recent scheme for Unicef wins an award, that comes as a genuine surprise. Believe me, winning awards is the last thing on my mind these days. Most designers working full-time in identity and branding probably expect to win less prizes. It seems to come with the territory.

Branding. In Five and a Half Steps: The Definitive Guide to the Strategy and Design of Brand Identities

Michael Johnson

29th September 2016 | c. 1,000 illustrations

Size: 24.5 x 21 cm | Hardback £29.95 | Extent: 320pp | ISBN: 978 0 500 518960

Thames and Hudson